Forget Perfectionism, Embrace the Chaos

In my previous two pieces in this series, I talked a bit about how startups are an exercise in controlled chaos, and how building an enduring franchise means getting very comfortable with ambiguity. That’s easy to say, and easy to nod your head along to. But it’s much, much harder to truly understand the full extent of unexpected situations that can pop up — and how to handle them.

As Mike Tyson said, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” And startups are all about getting punched in the mouth. Except in startup land, you rarely even know who or what is throwing the punch, which direction it’s coming from, or even that you’ve stepped into the ring.

Continuing the thread from the previous pieces, I want to share some of the punches we were dealt building NerdWallet, and some of the lessons I’ve picked up over the years that I apply when working with founders within the BTV portfolio.

We built The Mint around these lessons, helping fintech startups navigate the zero-to-one phase and arm themselves for their own journeys.

Two steps forward, one step back

On Memorial Day weekend in 2010, my wife and I were leaving New York to pursue my startup dreams in San Francisco. We’d packed all our stuff into a moving truck, then we, my NerdWallet co-founder, Tim, and a bunch of our other friends took a trip to Barbados as a goodbye, and perhaps, our last vacation for a while.

Right when we got there, Lifehacker released a feature on us – a positive review on the depth of cards and banks featured in our credit card reviews. What a way to start our vacation! It was an exciting moment, the first real validation of what we spent so many tireless months putting together. We’d actually been picked up by Money Magazine and by the New York Times at this point, but Lifehacker was our people, and it sent more traffic to us on the first day than both of those combined.

It was a big moment for our young company – until our website crashed.

The cheap dedicated server we rented from some random company we found online, and maintained ourselves, buckled under the weight of our newfound traffic. You see, at this point, we were basically just some PHP spaghetti code that we FTP’ed to a computer in a room somewhere, matched with a SQL database that we manually updated from an Excel spreadsheet. None of it was configured for speed or scale. And we didn’t have an engineering team, or DevOps, or anything like that. It was just us.

As Tim says, “Apparently, client-side rendering and database indexing didn’t matter when you had two visitors a day."

So, Tim and I sat in our swim trunks, on the patio, with our laptops out, trying to figure out how to get our server back online from the Caribbean Sea. Some way to start our vacation. Our early win had turned into a disaster.

Eventually we figured it out, got the site up, got a ton of traffic, and got some early brand validation, which helped us maintain momentum for a while. We also probably learned more that day than we had in months, which helped us prep the company for its next leg of growth.

There’s almost always going to be another shoe to drop; you have to take the wins and the losses in stride, learn from them, and get better every day.

It’s not important until it becomes essential

Although our vacation was upended by our servers cratering, in retrospect, it was a good problem to have at just the right time. In that moment, we thought, “Why aren’t we renting better servers?” But that’s just hindsight thinking. For a company with limited capital, it makes perfect sense that we waited until we needed to upgrade — to make both the capital investment and the investment of our time to understand better options for servers.

Things like Rackspace and AWS existed, and we knew a lot of ways to improve the efficiency of our code and our databases. But that all cost time and money, trade-offs we chose not to take until we had to.

Startups are in constant firefighting mode, which helps clarify the best use of your limited time and resources. In the early days, Tim used to ask me why I was wasting time with things like closing our books each month or paying our taxes. “We aren’t making any money anyway, and if we fail, it won’t matter,” I recall Tim saying. “If we succeed, we can just pay the penalties later.”

Once we got to the point where we had enough revenue to start hiring people, every new employee’s first suggestion was to redesign the website because it, objectively, looked like shit. Tim would always say, "No one's visiting our website, so who cares? Focus on building links and getting traffic, and then we'll worry about what the website looks like."

We were building our success through getting Google search traffic to individual pages, we weren’t a destination website – yet. Once the volume of traffic to the site made it worth prioritizing a redesign, and we could actually afford design and engineering resources, then we could rationalize spending our limited time there.

Every company faces its own constraints and its own trade-offs, so I don’t necessarily recommend taking the same approach that we did. But it goes to show that everything should be questioned, and anything is on the table in pursuit of hyperfocus.

There are generally only 1-to-3 things that matter for a startup at any given time, and you have to learn to let all the other fires burn, no matter how painful that is.

Perfect is the enemy of good

In this series, the big theme we’ve been exploring is the need for startup founders to shake off the funding shellshock and unlearn the bad habits from the era of easy capital, such as splurging on spending for things you think you need – hiring a bunch of positions, making capital outlays for office and equipment – before reality tells you what you actually need.

Flagrant spending at the start of the startup journey is also a byproduct, I think, of a strong streak of perfectionism found among people who want to start their own tech company. The people who start companies tend to have very Type A personalities. They want to skip the gloriously messy part of company formation and jump straight to what they think a company should look like. They’re “playing startup.”

We mostly grew up a certain way, and we like our lives to be very linear: “If I do this, then I do that, then I succeed.” That may work through high school and into college, and it works in the corporate world. But once you hit the wilds of the actual startup world, that approach becomes a liability.

Stepping away from perfectionism is hard for a lot of founders. But that’s what startups are: semi-controlled ambiguity. And those who excel at startups are those who thrive in not knowing the answer to every question, but instead will just say, “f*ck it, let’s just try it and figure it out."

I remember one of my conversations many years ago with Drew Houston at Dropbox, who was always a few years (and a few billion in enterprise value) ahead of me in the founding voyage. He told me something along the lines of, “No matter what you read, or how often people tell you they’re crushing it, every company is screwed on the inside. You just have to be constantly working to make it better.”

This is actually the primary reason I like reading books about the history of household names like Google and Amazon. I don’t think you really learn anything actionable from most business books, but when you go back and hear the early stories, the one thing that’s constant is the embraced chaos; the quantity of things those founders messed up along the way, how chaotic those early organizations were, and how everyone thought they were crazy all the time. But they all picked the right market, they listened to it, and they adapted to it.

Kill your baby

Nothing we ever produced at NerdWallet was perfect on day one, which is another issue I want to raise: People should view startups as experiments and learning machines. We all start with an idea, but ideas are worthless on their own. They should be relentlessly tested against the realities of the market, and then killed dispassionately in favor of whatever is working best. Darwinism at its finest.

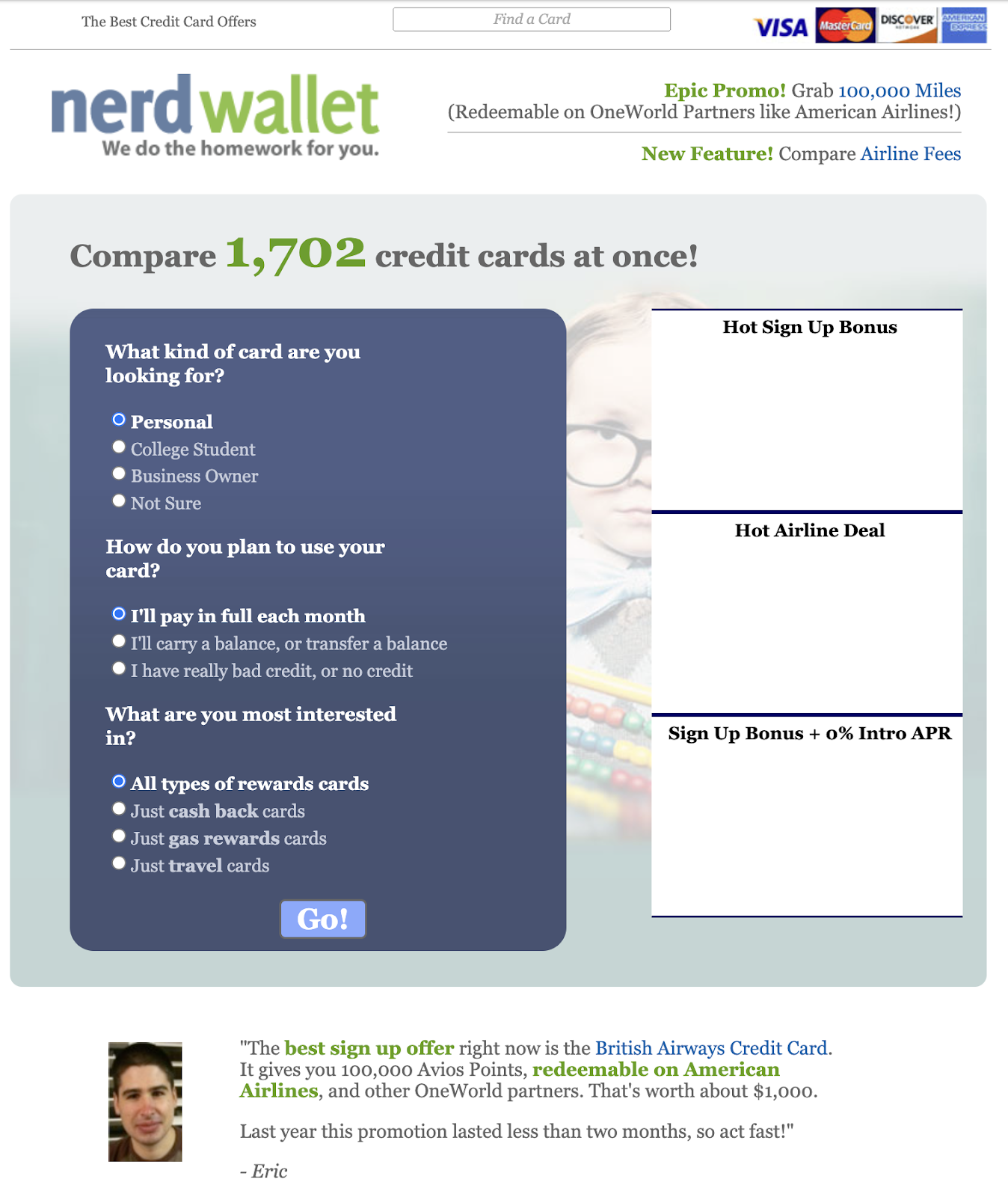

The original idea for NerdWallet was something like “Kayak for credit cards” (please withhold judgment, this was a long time ago). And while that product still somewhat exists within NerdWallet, we learned quickly that what we really needed to build was a marketing machine. Financial products run on advertising, it’s not necessarily the best product that wins, and “if you build it, they won’t come.” So we started to think of our product solely as an extension of our marketing, and we built the entire business around that instead.

It wasn’t sexy. No one wanted to work on an SEO machine, people wanted to build glittery products that got TechCrunch write-ups. But we were building a real business and wanted to make real money, and this is what worked. So, we doubled and tripled down until effectively all of our resources were dedicated to marketing in some form.

The idea that got you started won’t necessarily be the idea that brings you to a mass audience, so beware of falling too in love with your original idea. You pitch this story to yourself, your friends and family, would-be investors and employees, and it becomes an example of sunk-cost fallacy; you feel like you’re stuck following that original path. But if people aren’t buying what you’re selling, you feel like you’re pushing a rock up a hill; and the market isn’t dragging you along, you’re on the wrong path.

When your original idea doesn’t pan out, that can be dispiriting and can threaten the motivation that set this journey into motion. Here, I’m reminded of what David Goggins, the ultramarathon runner and former Navy SEAL, says about motivation versus drive: “Motivation is crap. Motivation comes and goes. When you are driven, whatever is in front of you will get destroyed.”

Motivation is something that strikes when you're comfortable, but drive and obsession push you to do things you didn't think you were capable of. And that means running through walls, killing what doesn’t work, and driving hard at whatever you find that does work.

Experimentation is a culture

Convincing yourself to pivot from your original idea is hard enough, but imagine going to your teams and saying, “This isn’t working, we’re going to do this other thing.” and their response being, “Wait, what the f—? We’ve spent all this time working on this thing!”

Once you hire, surrounding yourself with employees who embrace a culture of experimentation can be tough. But that’s what worked at NerdWallet. I won’t lie, it’s chaotic. We would throw spaghetti at the wall, then something successful would emerge, and we’d double down and go with that. And then there's more chaos.

We never had a fixed vision of what NerdWallet should be, like, “This is what it is, and once we build it we just need to figure out how to sell it this way.” The market always trumps your initial idea, so we made it a point to listen to the market.

That had to be built into the culture. It permeated every aspect of the business, not just the product.

Stay lean as long as possible

This has been a repetitive mantra in these posts, but experimentation, embracing chaos, pivoting and adapting are all so, so so much easier if you can stay lean and do as much as possible with a smaller team of missionaries. No one will embrace the ambiguity, feel the ownership, and be as obsessed with solving the problem as you and your founding team.

Keep that as long as possible. Startups are learning machines. You will have to be a learning machine. And every time you delegate that responsibility elsewhere, hire "experts" to build your company for you, or try to control the chaos with overbuilt processes, you run the risk of impeding your own learning process and impeding your growth.

This is guerilla warfare. Embrace it!